Finally, some changes to health-based discrimination in Canadian immigration law

Published: May 14, 2018

As it stands, there is health-based discrimination in Canadian law. The system disadvantages the diseased and disabled.

Restrictions preventing people with disease and physical or mental challenges from permanently immigrating are longstanding features of how Canadian borders have been and are enforced. Applicants for permanent immigration are ineligible if state-employed physicians anticipate their care and treatment to be above $6,655 a year.

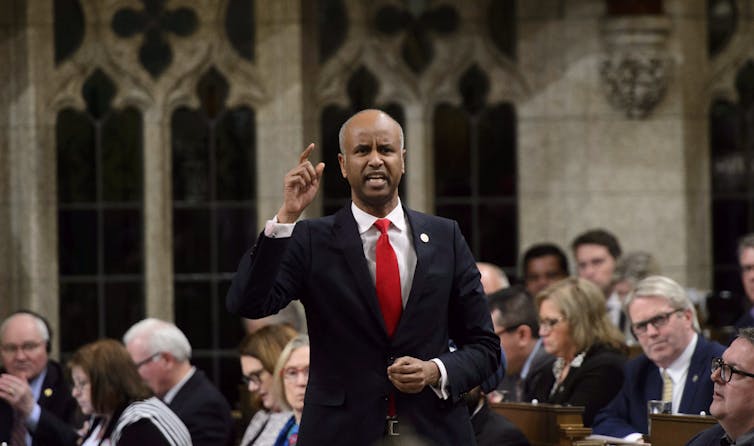

On April 16, federal Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen announced that there will be , the section of the law that deals with ‚Äúmedical inadmissibility due to excessive demand.‚ÄĚ

The three changes are:

-

The financial threshold for excluding applicants was increased to $20,000 a year.

-

Speculated future cost of care on public social services no longer applies.

For years in Canada there has been collective mobilization to repeal Section 38-1-C. To date, there have also been two Charter of Rights and Freedoms’ challenges aimed at eradicating health-based discrimination in Canadian immigration law.

Work on this issue has accounted for thousands of working hours for persons directly affected by exclusions, their allies and civil servants. .

While the government of Canada publicly agreed with this position, it decided against full repeal. The country is thus not compliant with its domestic and international human rights obligations, including Article 18 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which deals with human mobility.

My decade of researching and has been illuminating. I have learned that we teach immigration history so poorly that year after year, students arrive in my classes unfamiliar about how the Canadian immigration system works.

This is not entirely surprising because the system is an immense bureaucracy. We know that .

.

Respecting human rights is good policy

Less frequently addressed in headlines is that the immigration system provides a steady source of income for professionals inside and outside Canada. Lawyers, doctors and administrators benefit from a system that is simultaneously opaque and structured to depend on their professions. In fact, removing Section 38-1-C would curtail sizeable and ongoing legal, medical and administrative costs.

Newcomers to Canada with whom I have talked about medical inadmissibility are animated when discussing their experiences with lawyers and doctors associated with the immigration system. However, the public is generally poorly informed about how the system works, including how much money it costs people to immigrate.

Ethical and moral forms of reasoning chronically have a hard time competing with economic imperatives. But for a fiscally concerned Canadian public interested in weighing in on anticipated future costs of caring for and treating people, whether immigrants or otherwise, we must remember to see whose interests are served by the current law.

That is, we must not reinforce the binaries of economic imperatives and morality. They are false. . Furthermore, people with disease and disability contribute to all societies everywhere in qualitatively and quantitatively measurable ways. This is indisputable.

We might stop and reflect on the circumstances of our own families. We are endowed with road maps for how to quantify human contributions.

Take, for instance, domestic labour. Work in the home is taken for granted unless we make it visible. Seeking to make gendered work count in market terms led to New Zealand public policy professor Marilyn Waring becoming a pioneer in feminist economics. .

Rethinking health and illness

New lines of advocacy for repealing the IRPA Section 38-1-C are needed. Within disability studies, ideas about people with disease and disability, who have long been portrayed as ‚Äúother‚ÄĚ and as vulnerable, .

Looking at health and illness as tentative, conditional, as a matter of geography, is helpful. For one thing, this compels us to reflect on how we think and talk about people with disease and disability. It channels us towards a reflexive stance, and offers us the opportunity to consider how we all experience vulnerability.

New approaches to assessing immigrant applications are needed. First, the diseased and disabled should not be pre-judged or ruled out for admission to Canada based on economic assessments alone; instead, their vulnerability should be considered a skill and a coveted source of strength.

.

For example, refugee applicants, in particular, settle after enduring and overcoming chronic existential uncertainty and protracted material depravity. They have acquired skills that make them resilient and hard-working.

These are exactly the human attributes that Canada wants in prospective immigrants through its immigration program. Going forward, most Canadians will have settled in Canada using the immigration system.

The Canadian public surely must be curious about how immigration works. We should know more about what our fellow Canadians had to do permanently settle here. We have much to learn from would-be immigrants and their experiences.

What are next steps? Collective action to repeal the IRPA Section 38-1-C will continue. We will resume generating scholarly and experiential evidence to support a full repeal. It is not a matter of if a full repeal will happen, but rather when this will occur.

is an assistant professor of health studies at ļ¨–Ŗ≤›īę√Ĺ Scarborough.

This article was originally published on . Read the .

![]()